Using this post (this specific one) to post sections for proofreading.

Just the intro so far. I wanted to glaze over the background, and give most that would read this a jumping off point before adding too much other stuff.

Still need to add links and make some revisions giving credit to those who helped me out with this (

@deathbypsi and another person on Facebook).

Feel free to be critical, suggest edits, and correct mistakes. I don't get butthurt, and I mostly wrote this when bleary-eyed and dealing with insomnia. Theres going to be some stuff in here that needs to be edited.

Megasquirting a 2.9

Original Poster: PetroleumJunkie412

Difficulty: Varies by engine and type of Megasquirt/Microsquirt utilized. Varies from a 2 out of 10 to 10 out of 10. My specific case has been a 7/10 since there was very little tuning and engine management information available on the 2.9 when I started.

Time to install: Varies. My installation took approximately 4 – 6 hours, but I had to work out many electronics bugs and re-solder my main board several times.

The other costly time factor is the tuning process. This can take as short as a few drives, to several trips to the dyno.

Depending on the route you take, the total time to install can be as lows one hour for engines like the 5.0 and 302 (should you opt for a pre-tuned Microsquirt and plug-and-play adapter harness), all the way to a months long process, complete with tuning and fabrication extravaganza. For engines that are “close enough” to a well-known one (like the 2.9 and the 302 of the same era), and with an unassembled kit like mine (a DIYPNP 1.5, which is a Microsquirt module on a control board and an adapter board) plan for a minimum of 4-6 hours, plus assembly time of the boards. As I discovered, the time factor can vary wildly when working with less researched or modified engines. If you are considering going “all out” and building a Megasquirt II or III from scratch, plus adapting it to an engine never available as fuel injected, plan for a steep learning curve, lots of fabrication and adaptation work, and countless hours spent researching engine theory, history, etc. More on the differences in aftermarket ECMs below.

Disclaimer: The Ranger Station.com, The Ranger Station.com Staff, nor the original poster are responsible for you doing this modification to your vehicle. By doing this modification and following this how-to you, the installer, take full responsibility if anything is damaged or messed up. If you have questions, feel free to PM the original poster or ask in the appropriate section of The Ranger Station.com forums.

Brief Explanation:

I do not want to run off in too many tangents with this article, and would prefer to focus on the technical details, as there are many. I would strongly recommend (if I could, I would “require”) those pursuing this project to read as much history as they can find on the advent of engine governance.

Warning: Tangent

An incomplete timeline of the topic would include the days of steam, early gunpowder metered engines, hit and miss engines, carburation and mechanical fuel injection, and into the modern era of the varying types of electronic fuel injection (EFI).

With a firm grasp on the history of engine control and management, you’ll have a much easier time learning how to build and operate an engine control system quite literally ‘from scratch,’ and in learning how the intense number of parameters and control methods apply (or do not apply) to your project. I am still learning daily, and am by no means an expert, or even a novice. I’m just a guy with a truck and an engine that I like (despite ‘popular’ opinions of said engine).

The advent of Electronic Fuel Injection effectively “locked” many automotive enthusiasts out of the ability to modify engines beyond factory specifications. Early EFI systems were based on a variety of systems, one of which being Speed Density

Speed Density is a mathematical formula that allows an engine control computer (ECC/ECM/PCM, etc) to determine the amount of fuel to inject based on data collected from the engine via an array of sensors. The system used on the 2.9l was Ford’s EEC-IV (pronounced “Eek-4”) Speed Density system which utilized data collected from sensors on the engine. These sensors measure the speed of the engine (RPMs), the intake manifold pressure (MAP), the throttle position (TPS), intake air temperature (IAT), Idle control valve position (IAC), exhaust gas oxygen (EGO, O2, etc), and engine coolant temperature (CLT). A fantastic explanation of this is from Ed Hohenberg’s article “

Tuning Your Ford EFI System – Inside the Black Box Part 1” found in Mustang 360.

I cannot recommend reading this article strongly enough to all of those seeking to Megasquirt (or do ANY tuning to ANY EFI engine) their vehicle. This is the article I started actually learning from, and started to grasp real understanding of how to modify or build their own ECM.

“Here's how SD works: The ECU will first sense MAP and IAT. Using the ideal gas law, it can calculate the instantaneous inlet air density (hence the "density" in SD). From the engine rpm and MAP, the ECU will look up (interpolate, if necessary) the programmed VE. Using the VE, engine displacement, and rpm, the ECU can calculate the instantaneous mass airflow into the engine. Looking up the desired A/F ratio from the base fuel table, the ECU will calculate the required mass fuel flow to achieve the desired A/F ratio. Knowing the number of injectors, and flow rating of the injectors, the ECU can calculate the required DC for the injectors. Finally, knowing the DC and rpm, the ECU can calculate the required PW for the injectors. Whew!

Let's illustrate with an example. Let's say we have a 5.0 engine operating at a manifold vacuum of 5 in Hg., rpm of 3,000, IAT of 80 degrees Fahrenheit, desired A/F ratio of 14.6, and it has eight 19-lb/hr injectors. For these conditions of rpm and MAP, the VE table calls for 85 percent.

After 1999, Ford went to a returnless fuel system. Said system is found in any stock '03-'04 Cobra. A fuel rail pressure sensor (found on the driver-side fuel rail), monitors the fuel pressure, so the ECU can regulate the fuel pumps as necessary to maintain a constant pressure drop across the injectors.

From the ideal gas law, D = p/(RT), where D is density, p is absolute pressure, T is absolute temperature, and R is the gas constant for air. Before we can calculate the density, we need to fix the units so it all works. To save our sanity, we'll do the calculations in metric units. For the air temperature of 80 degrees F, the absolute temperature would be 300 degrees Kelvin. For an intake vacuum of 5 in. Hg, the absolute pressure would be 29.92-5 = 24.93 in. Hg. = 84.42 kPa. In metric units, R = 0.286 kJ/kg-K, the injectors would flow 8.36 kg/hr and the CID would be 0.005 m3.

So our inlet air density would be: D = 84.42/(0.286*300) = 0.984 kg/m2. Mass air flow is then: Ma = 11/42 D (VE)(CID)(RPM) = 11/42 (0.984)(0.85)(0.005)(3,000)= 6.72 kg/min. For an A/F ratio of 14.6, the fuel flow must then be: Mf = Ma/14.6 = 6.72/14.6 = 0.43 kg/min.

For eight injectors, each would need to flow 0.43/8 = 0.054 kg/min = 3.2 kg/hr. Since the injectors can flow 8.36 kg/hr when wide open, we only need an injector duty cycle DC = 3.2/8.36 = 0.385 or 38.5 percent. For a four-stroke engine (two revolutions per intake event), the time interval between intake events is t=2/rpm (in minutes) or 120,000/rpm (in milliseconds). At 3,000 rpm, the interval is then t=120,000/3,000 = 40 ms.

Finally, the required injector pulse width, PW = DC(t) = (.385)(40) = 15.4 ms. Isn't math fun?”

Hohenberg’s article explains a few key things about Speed Density systems that illustrate why engine modifications made with an EEC-IV controlling the engine do not always add up to additional power. Also, this explains why an EEC-IV engine cannot have any major power adder work done (bore and stroke modification, supercharger, turbocharger, etc.) without also providing a way to modify fueling. The EEC-IV is already pre-programmed to run a factory determined amount of fuel and spark advance for the engine at any given position on the throttle and RPM. The volumetric efficiency, injector size, displacement, air filter style, and restrictions within the intake and exhaust pathways are pre-calculated at the factory, and without a way to re-program, or “tune,” the ECM, there is no way for the computer to “see” changes that you’ve made. Even if your butt-dyno tells you that your headers or your K&N intake are making your truck ‘30hp over stock’ and ‘hook up better for launches,’

without a programmable or tunable ECM, you are always leaving power on the table and not taking advantage of money spent and modifications made.

So what the heck is a Megasquirt? Microsquirt?

Warning: Tangent

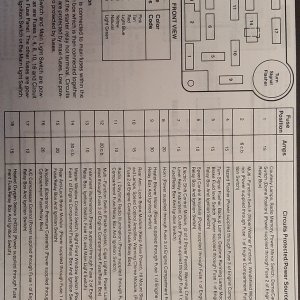

The Megasquirt and Micrisquirt (along with Holley EFI, Speeduino, and many other systems) are standalone aftermarket ECMs – they are engine control computers that allow for a vast array of different fuel and air programs, engine management strategies, and essentially any power adder you can dream up. The capabilities of these systems range from something as simple as upgrading injectors on a 302, all the way to custom fabricating a W24 engine out of two BMW M60 blocks, and then adding supercharging, turbocharging, methanol injection, sequential stacking fuel injectors, nitrous shots, and an electric hybrid drive for good measure (because why not break the sound barrier while we’re at it). No matter what you dream up, one or more of the aftermarket standalone ECMs covers the project.

The beauty (and fun, in my opinion) of these systems is they give the user COMPLETE control of their engine and the ability to modify and change their programming ad nauseum. Every parameter, every sensor, every management strategy can be modified and adjusted, along with the sensors that collect data from the engine. In my specific case, my 2.9 has been modified, with many more modifications to come. The Megasquirt/Microsquirt system that I chose allows for me to keep building and modifying to the engineering limits of a V6.

Personal experience that highlights the degree and ease of control that a standalone ECU gives the user is that I switched from the factory 14lb single port fuel injectors to 24lb Saleen quad port injectors in two keystrokes and five mouse clicks (I counted). I also switched from the stock Ford frequency-based 1 bar map sensor to a GM voltage-based 3 bar map sensor and a secondary live barometric sensor (this allows my ECM to recalibrate AFR based on barometric pressure/altitude once per millisecond) with three wire splices, two re-soldered wires on my main board, six mouse clicks, and eight keystrokes.

The Megasquirt and Microsquirt (and their individual versions) are far too much to cover with a tech section write-up. There are several books on them, and many forums and tuning sites dedicated to discussing ways to set up and utilize them for any number of projects.

In order to pursue a project like this, please first read the Hohenberg articles, and then do some browsing on the internet on standalone EFI systems, and which one best fits your needs.

In the case of my project and budget, the DIYPNP 1.5 was the overall winner, as it would allow me to run the 2.9 as natural aspiration for now, and allow for the easy installation of a power adder/adders (forced induction) with water/methanol injection. Should I change direction, or even opt for an engine swap, the Megasquirt can be transplanted into any other TBI or MPI engine out there with the use of an adapter board, and has the to control things like nitrous and a dizzying amount of other power adders. Overall, for a 2.9, it was the best bang-for-my-buck.

http://www.mustangandfords.com/project-vehicles/0607mmfp-ford-efi-system-tuning